Overview

The Chicago Orphan Asylum was formed on 3 August 1849 as a response to the death and displacement caused by the worldwide cholera epidemic.[1] The Orphan Asylum was organized by a group of leaders in Chicago who were predominantly Protestant and early settlers of the city, including William B. Ogden, Orrington Lunt, Walter S. Newberry, William H. Brown, John H. Kinzie, and J. Young Scammon.[2] Ogden was Chicago’s first mayor and Newberry later became mayor of the city. Daily operations were managed by a board of women called the Board of Directresses.[3]

The official incorporation date of the Chicago Orphan Asylum was 5 November 1849.[4] The mission adopted in its incorporation was “the protecting, relieving, educating of, and providing means of support and maintenance for orphan and destitute children.”[5] According to author Mrs. Sarah Wheeler, “it was determined that no child should be bound out to service under ten years of age, but could be adopted at any time. It also permitted children of soldiers in the army, or who had been in the service of the United States, to have home in the asylum.”[6]

The first three children were admitted to the asylum on 11 September 1849.[7] The first home that the Orphan Asylum operated out of was originally in the house of Mrs. Ruth Hanson, the first Matron of the Orphan Asylum, which was situated on Michigan Avenue between Lake and Water Streets. [8] However, after a few months of fundraising, the asylum moved to Adams Street, between State and Dearborn Street, into a frame house.[9]

A short time later, the asylum moved to the Hinton House on Wells Street [Fifth Avenue], between Van Buren and Harrison Streets.[10]

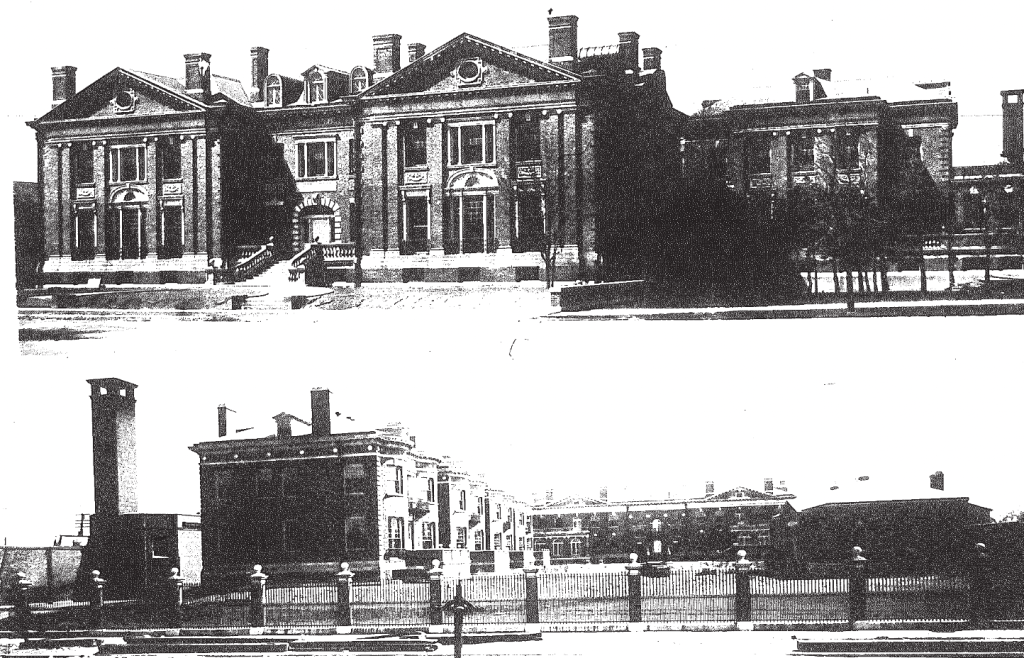

Around 1850, Mr. Johnson donated a lot of land on the north side of the river to erect a permanent building and the Orphan Asylum expanded the size of the campus by buying the surrounding land.[11] The orphanage moved in 1853 to this site, 2228 South Michigan Avenue, into a three-story brick building designed by Burling and Baumann.[12] The building was enlarged in 1884 with the addition of Talcott Hall.[13]

After the Great Chicago Fire, in October 1871, the Chicago Orphan Asylum opened its doors to assist men, women, and children. A depot for clothing distribution under the auspices of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society was set up in the parlors of the asylum and a temporary sewing room was created in a school-room for the use of a sewing society for the employment of women who lost their jobs due to the fire.[14]

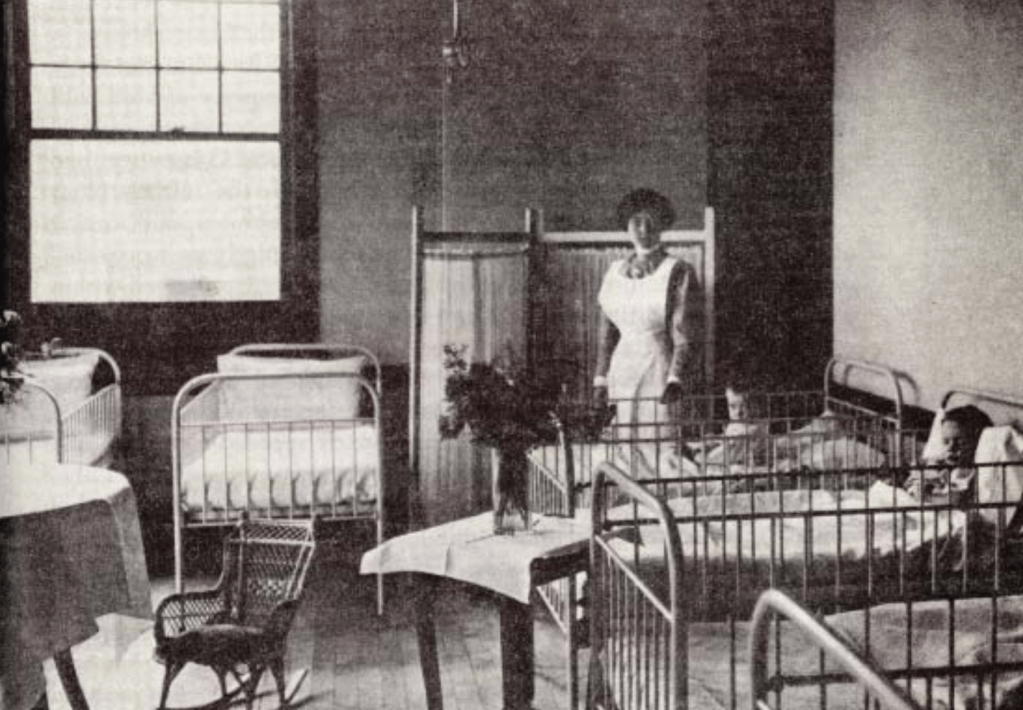

The addition of Talcott Hall in 1884 included an addition to the school room and increased accommodations to a capacity of 250 children.[15] The Chicago Orphan Asylum included a school since before 1877.[16] However, as more children were admitted, it became necessary to re-organize the school and model it after the public schools in Chicago. So, secondary and primary departments were created.[17] In 1882, a primary department and kindergarten was established, which opened with an attendance of 40 children from five to seven years old.[18] In December 1883, a kindergarten opened, and it was presided over by teachers connected to the Free Kindergarten Association.[19]

In 1887, the Board of Directresses decided that all children who could pass the required exams for the third grade would be sent to the Chicago public schools.[20] Several students were able to pass and were transferred to the Mosely School and the Chicago Manuel Training School took one of the boys from the orphanage as well.[21]

Around 1891, the Chicago Orphan Asylum was maintaining three schools, with an average attendance 150 students.[22] By 1892, the School Committee of the Board of Trustees decided that all children over seven years old were to attend the public schools.[23] Upon this decision, the school departments of the orphanage were organized into one department: Kindergarten Primary.[24]

The Chicago Orphan Asylum also ran an industrial school. In 1874, a sewing school was established in the orphanage by the Directresses of the Board of Trustees for the education of both boys and girls.[25] The sewing school was later changed into an industrial school, which included sewing for the girls and the employment of a printer to teach typesetting for the boys.[26] In March 1890, it was decided to modify the plans for the industrial school, as many of the older children were attending the public schools and unable to be present at the regular class times.[27] Thus, shortly after, the Industrial School within the orphanage was closed.

On 18 November 1879, Former President Ulysses S. Grant visited the Orphan Asylum and met with the children.[28]

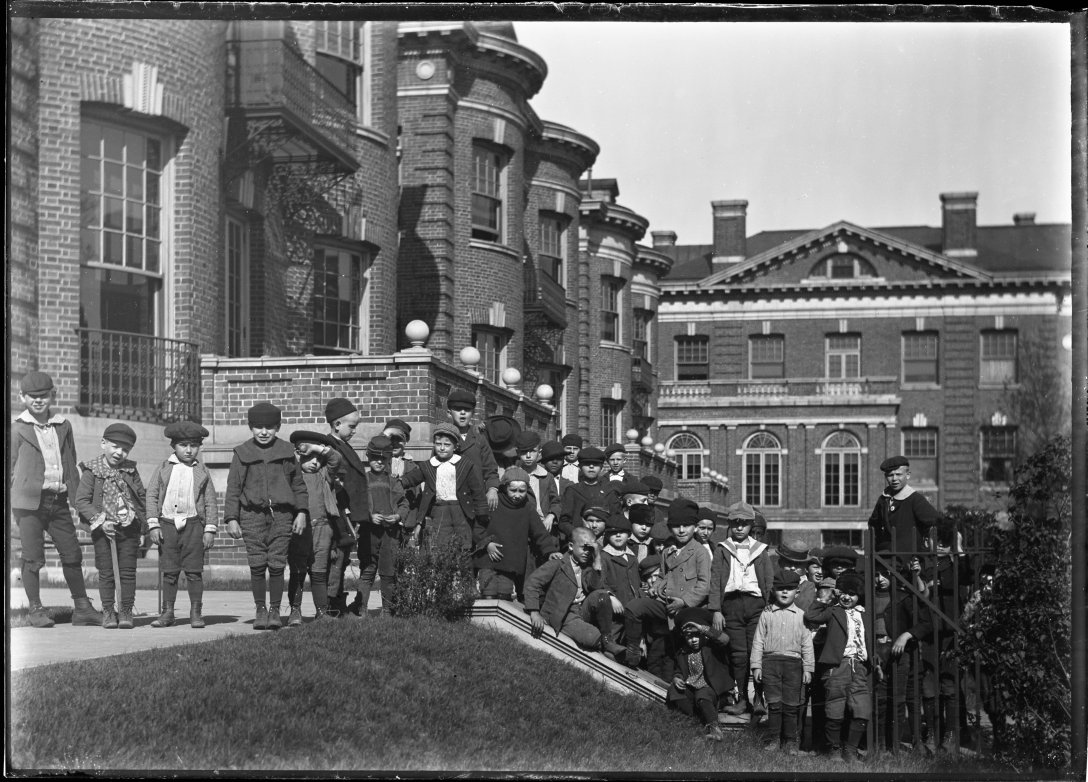

In 1899, the Chicago Orphan Asylum moved to 5120 South King Drive. At the time, the street was named “South Park Avenue,” but it was later renamed after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This building was designed by the architects at Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, who also designed the Allerton Wing of The Art Institute of Chicago and the original Chicago Public Library.

By the 1920s, due to changes in child-care practices and social welfare, the Chicago Orphan Asylum changed its mission from large-scale institutional, residential care for children to smaller-scale living arrangements. The Orphan Asylum moved its remaining children to a smaller rented building at 4911 South King Drive (then South Park Avenue), which has since been demolished.[29] By 1938, the Chicago Orphan Asylum began a foster care service.[30] By its 100th anniversary in 1949, the Chicago Orphan Asylum was no longer an “asylum,” as it had changed it “adopted a plan for providing foster home care for babies and children up to 6 years old.”[31]

After moving out of 5120 South King Drive, the Orphan Asylum sold the building in 1940 to the Good Shepherd Community Center, which became a significant institutional anchor in the Bronzeville community and was strongly associated with the literary and artistic movement of the 1930s and 40s known as the “Chicago Black Renaissance.” In 1957, the Chicago Baptist Institute purchased the building.[32]

The Orphan Asylum continued operating through adoption and foster care work. In 1949 it changed its name to the Chicago Child Care Society (CCCS) and later CCCS merged with Family Focus.

Institution Name and Type

Alternative Names: Chicago Protestant Orphan Asylum[33]

Type of Institution: Agency, Foster Care, Industrial School, Orphanage

The industrial school was closed shortly after 1890 (see overview for details).

By 1938, the Chicago Orphan Asylum began a foster care service.[34]

In the later years of the twentieth century, the Chicago Orphan Asylum became more focused on adoption placement, foster care, and education.

Location and Building

Address:

1849: Michigan Avenue between Lake and Water Streets, frame house

1849: Adams Street, between State and Dearborn Street, frame house

1849-1850: Hinton House on Wells Street [Fifth Avenue], between Van Buren and Harrison Streets

1850-1899: 2228 Michigan Avenue.[35][36][37][38]

1899-1940: 5120 South King Drive[39]

1940: 4911 South King Drive

1942: 850 East 58th Street

1949: 5494 Kenwood Ave.

Locality: Chicago

County: Cook County

State: Illinois

Notes on the buildings: The building at 2228 South Michigan Avenue that housed the Chicago Orphan Asylum from 1853 to 1899 was sold by the Orphan Asylum in 1899.[40] The building was torn down in the early 1920s to make room for the Marmon and Hudson Automobile Showrooms, which are now contributing to the Motor Row Chicago Landmark District.[41] The building at 5120 South King Drive still stands and is occupied by the Chicago Baptist Institute.

Administration Information

Date of Founding: 1849

Dates of Name, Place, Mission Change, or Merger:

- After March 1890: The industrial school was closed as more children attended the public schools

- By 1930, the Chicago Orphan Asylum began a foster care service and by 1942 was no longer a residential institution..[42][43]

- 1949: changed name to Chicago Child Care Society

Successor: Chicago Child Care Society

Date of Overall Closure: Not applicable. Chicago Child Care Society merged with Family Focus in 2001 and still operates today.

Administration:

- 1910: Private corporation

- 1923: Protestant churches

Contributors/Support:

Endowments, Tolcott Fund, Private contributions

The Froebel Association assumed the expenses of the school after 1883.[44]

Benefactors during the early years:[45]

- Jonathan Burr, $11,760

- Flavel Mosely, $10,000

- William H. Brown, $1,000

- Mrs. Funk, $500

- Thomas Church, $1,000

- Josiah L. James, $5,000

- Allen C. Lewis, $4,000

October 1871- April 1872: the asylum received $400 a month from the A. T. Stewart Relief Fund to provide for the “maintenance of children whose widowed mothers were dependent upon themselves for support.”[46]

April 1872: $10,000 from the Executive Committee of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society.[47]

After 1881: Mrs. Mary H. Talcott, donated over $5,500.[48]

1883: M. E. Gulliver, $1,000.[49]

1889: John A. Rottchild, $500; Philetus W. Gates, $4,000; Mrs. Sarah C. Sayrs, $100.[50]

1890: Conrad Seipp, $5,000; Tolman Wheeler, property valued at $10,000.[51]

1891: A. Goldsmid, $150.[52]

1892: John Crerar, $50,000.[53]

Notable People

Rev. Charles V. Kelley: rector of Trinity Episcopal Church and physician who volunteered in the early years of the orphanage.[54]

Mrs. Mary H. Talcott: benefactress[55]

Leonard Hodges: appointed to the Board of Trustees in 1880.[56]

1853 Directresses[57]

Mrs. J. H. Kinzie

Mrs. J. C. Haines

Mrs. P. Carpenter

Mrs. R. J. Hamilton

Mrs. J. Beecher

Mrs. S. Brooks.

Mrs. Dr. Dyer

Mrs. N. H. Bolles

Mrs. J. Murphy

Mrs. S. Marsh

Mrs. E. Nicholson

Mrs. T. Church

Mrs. Dr. Boon

Mrs. H. Horton

Mrs. R. McVicker

Mrs. H. Porter

Mrs. S. J. Surdam

Mrs. C. N. Holden

Mrs. C. Follansbee

Mrs. Dr. Pitney

Mrs. Chas. Walker

Mrs. D. M. P. Davis

Miss Julia Rossiter

1853 Officers[58]

William H. Brown, President

Orrington Lunt, Vice President

D. S. Lee Esq., Secretary

Richard K. Swift, Treasurer

1853 Trustees[59]

Thomas Dyer

William B. Ogden

J. Y. Scammon

John H. Kinzie

J. K. Botsford

W. L. Newberry

B. W. Raymond

W. M. Jones

Sylvester Lind

J. H. Woodworth

P. Von Schneidan

Presidents of the Board of Directresses[60]

Mrs. J. H. Kinzie

Mrs. D. J. Ely

Mrs. Dr. C. V. Dyer

Mrs. A. Vail

Mrs. Henry Sayrs: 1872-1874, 1879-1881

Mrs. Dr. A. Pitney

Mrs. Henry Fuller

Mrs. Tuthill King

Mrs. George C. Cook

Mrs. O. D. Ranney: 1875-1878

Mrs. Norman T. Gassette: beginning in 1882.

Matrons[61]

Mrs. Hanson/Mrs.Hansen: the first matron, who assumed duties in 1849.

Mrs. Charles Follansbee: helped Mrs. Hanson with the children in 1849.

Mrs. Jerome Beecher: helped Mrs. Hanson with the children in 1849.

Miss Fleming: Matron in 1851-1853.

Mrs. Watson: Matron in 1854-1856.

Mrs. Mary Handy: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Miss N. F. Hill: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Mrs. Jones: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Mrs. Whittier: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Mrs. O. G. Darwin: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Mrs. C. M. Grout: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Mrs. Burns: Matron sometime between 1857-1867.

Miss Emily Swan: Matron from 1868 to September 1873.

Mrs. H. C. Bigelow: Matron from 1874 to at least 1892.

Mrs. C. N. Stocking: Matron

Intake Information and Requirements

Intake Gender/Sex: Female, Male

Intake Age:

- 1872: Birth-16 years old[62]

- 1892: “No age, race or condition have ever been turned unassisted away.”[63]

- 1892: “But of late years admission was confined to children from one to twelve years of age.”[64]

- 1910: Male max age 10, Female max age 12

- 1923: 1-12 years

- 1949: plan adopted to provide foster care for babies and children up to 6 years old, but in practice provided foster care for babies through 17 year olds.[65]

Intake Ethnicity/Race:

- 1892: “No age, race or condition have ever been turned unassisted away.”[66]

- 1904: “There is no race or color distinction with the children. Almost every nationality is represented among them.”[67]

- 1910: All

- 1923: White, Chinese, Japanese

Intake Specifics:

- 1872: “It was also determined to receive from the Courts vagrant and homeless children who were in no wise subjects for penal institutions, yet for whom no other places were provided. These were mostly children sent out by Eastern institutions and run-aways from home.”[68]

- Before 1892: “Many little ones have but one parent who cannot always provide a home for them, and so this asylum receives them to its homelike care, for which a small amount is paid each week. Here, again, we experience the wisdom of that kindly heart Judge Thomas, who years ago, when the project was first inaugurated, introduced the word ‘destitute’ in to the Constitution. He is not the only orphaned one whose parents sleep ‘life’s dreamless sleep.’ There is a deeper orphanhood than that, when father forgets his trust and fails to provide, and mother turns from her clinging offspring, while her heart gives no response to its helpless cry. Frequently these are as evidently cases for the reception of the charity of this institution as orphans themselves.”[69]

- 1892: “No age, race or condition have ever been turned unassisted away.”[70]

- 1892: Small amount paid for the board of children who parents place them temporarily in the asylum—regular price is $1.50 a week for each child.[71]

- 1910: Orphan

- 1949: Orphans, children under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court[72]

Number of Residents:

- 1849-1850: 100 children were sheltered in the asylum over the first two years.[73]

- 1851, December 19: 24 children[74]

- “Of these was a mute, whose silent language reached the soul with an appeal which could but awaken the tenderest sympathy.”[75]

- Between 1874 and 1892: over 3,680 children were admitted and 3,237 children were removed.[76]

- 1882: 40 children between 5-7 years old were educated in the primary school.[77]

- 1891-1892: 203 children, 170 were removed by their parents or friends, 10 adopted, 13 died.[78]

- 1892, September: 135 children from the orphanage entered public school.[79]

- 1922: 162 children in the home in November 1922, 255 cared for during the year.[80]

- 1949: more than 530 children cared for in foster homes by the Chicago Orphan Asylum.[81]

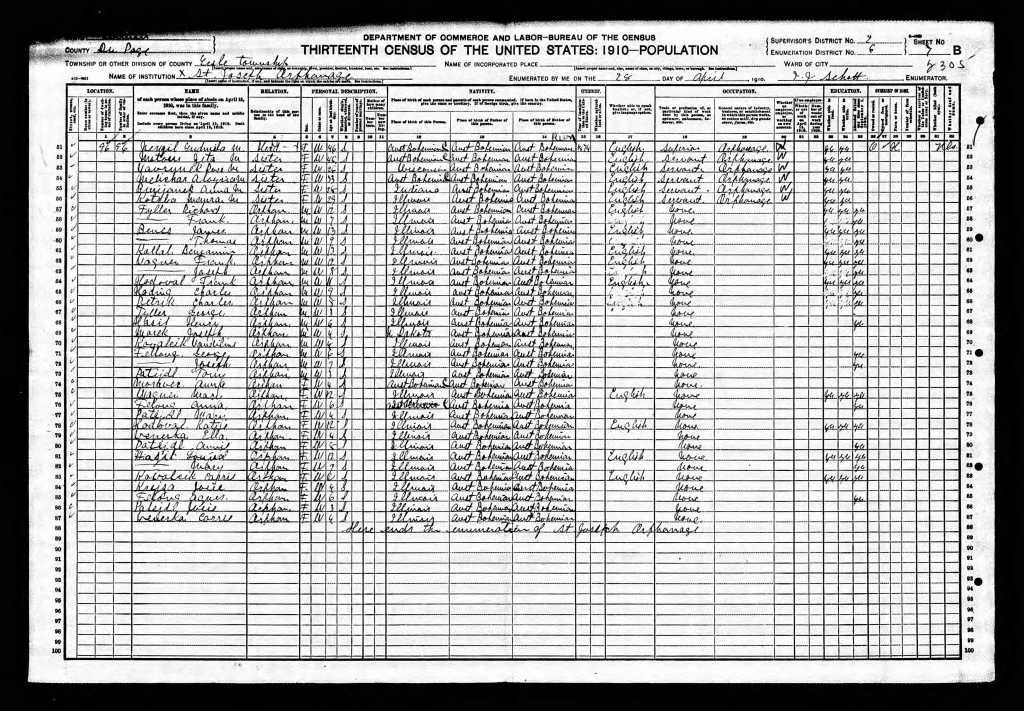

Records

“The number of children admitted to the asylum increases with every year. It became advisable for the reception committee, before whom persons came for admission, to keep an exact record of every child coming before them, its name and age, and name and nationality of parent or guardian. This plan has been faithfully carried out, and has been of great advantage in preventing imposition, and systematizing the work.”[82]

Online

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9377152/children-chicago_orphan_asylum

Annual Reports

Seventy-Third Annual Report of The Chicago Orphan Asylum for the Year Ending November 30, 1922. 1923. Chicago: Chicago Orphan Asylum. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofch7319chic.

Archives and Museums

Chicago History Museum

Chicago Orphan Asylum Records, 1871-1872. https://chhiso.ent.sirsi.net/client/en_US/public/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:237523/one?qu=1073020208&te=ILS&rt=false%7C%7C%7COCLC%7C%7C%7COCLC.

Newberry Library

“Rudolph Michaelis Glass Plate Negatives of Chicago and the Midwest, 1900-1905.”

- Includes two glass plate negatives of the Chicago Orphan Asylum

Books and Reports

Camp, Ruth Orton. 1949. Chicago Orphan Asylum, 1849-1949.

- Only known copy in a library is at the Chicago History Museum.

Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning. 2008. “Landmark Designation Report: Chicago Orphan Asylum Building, 5120 S. King Dr.” Chicago: City of Chicago. https://www.chicago.gov/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/Chicago_Orphan_Asylum_Bldg.pdf.

Wheeler, (Mrs.) Charles Gilbert [identified as Sarah Jenkins Wheeler]. 1892. Annals of the Chicago Orphan Asylum from 1849 to 1892. Chicago: Board of the Chicago Orphan Asylum. https://archive.org/details/annalsofchicagoo00whee.

Sources

A Guide to the City of Chicago. 1909. Chicago: The Chicago Association of Commerce. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Guide_to_the_City_of_Chicago/ZjgVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Board of State Commissioners of Public Charities. 1880. Sixth Biennial Report of the Board of State Commissioners of Public Charities of the State of Illinois, November 1880. Springfield, Illinois: H. W. Rokker, State Printer and Binder. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/OobIAAAAMAAJ.

—. 1884. Eighth Biennial Report of the Board State Commissioners of Public Charities of the State of Illinois, November 1884. Springfield, Illinois: H. W. Rokker, State Printer and Binder. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/DKTIAAAAMAAJ.

Chicago: An Instructive and Entertaining History of a Wonderful City. With a Useful Stranger’s Guide. 1888. Chicago: Rhodes & McClure Publishing Co. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Chicago/6VwVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning. 2008. “Landmark Designation Report: Chicago Orphan Asylum Building, 5120 S. King Dr.” Chicago: City of Chicago. https://www.chicago.gov/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/Chicago_Orphan_Asylum_Bldg.pdf.

“Chicago Orphan Asylum ‘Shoe Day’” 1903. Juvenile Court Record 4 (November 11): 7. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Juvenile_Court_Record/xpUqAAAAMAAJ?.

Cmiel, Kenneth. 2005. “Orphanages.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/937.html

Illinois State Charities Commission. 1911. Second Annual Report of the State Charities Commission to the Honorable Charles S. Deneen, Governor of Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Journal Company. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annual_Report/pFgZAQAAIAAJ.

Meinzer, Helen S. 1938. “Sources and Methods of Seeking Foster Homes Used by Seven Child Placing Agencies.” Child Welfare League of America Bulletin 23 (9): 1-9. https://archive.org/details/sim_child-welfare_1938-12_17_10/.

Moses, John (Hon.) and Maj. Joseph Kirkland (eds.). 1895. History of Chicago, Illinois. Volume II. Chicago: Munsell & Co. https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Chicago_Illinois/r78NAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Murphy, Richard J. 1892. Authentic Visitors’ Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition and Chicago. Chicago: Union News Company. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Authentic_Visitors_Guide_to_the_World_s/L8Y9AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

“Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

Riley, Thomas James. 1905. A Study of the Higher Life of Chicago: A Dissertation Submitted to the Falculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Literature in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chicago: The University of Chicago. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Higher_Life_of_Chicago/roo3AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Seventy-Third Annual Report of The Chicago Orphan Asylum for the Year Ending November 30, 1922. 1923. Chicago: Chicago Orphan Asylum. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofch7319chic.

United States Bureau of the Census. 1905. Benevolent Institutions 1904. Washington, D. C.: Governmental Printing Office. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Benevolent_Institutions_1904/GKpMAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

—. 1913. Benevolent Institutions 1910. Washington, D. C.: Governmental Printing Office. https://books.google.com/books?id=fmgGAQAAIAAJ.

—. 1927. Children Under Institutional Care, 1923: Statistics of Dependent, Neglected, and Delinquent Children in Institutions and Under the Supervision of Other Agencies for the Care of Children, with a Section on Adults in Certain Types of Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Governmental Printing Office. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=PFXZTGK-ZyAC&rdid=book-PFXZTGK-ZyAC&rdot=1.

—. 1935. Children Under Institutional Care and in Foster Homes. Washington, D. C.: Governmental Printing Office. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Children_Under_Institutional_Care_and_in/rnQGAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Wheeler, (Mrs.) Charles Gilbert [identified as Sarah Jenkins Wheeler]. 1892. Annals of the Chicago Orphan Asylum from 1849 to 1892. Chicago: Board of the Chicago Orphan Asylum. https://archive.org/details/annalsofchicagoo00whee.

Work, Monroe N. 1919. Negro Year Book: An Encyclopedia of the Negro, 1918-1919. Tuskegee, Alabama: The Negro Year Book Publishing Company. Page 398. Accessed through Google Books. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Negro_Year_Book/HqQwAAAAYAAJ.

[1] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning. 2008. “Landmark Designation Report: Chicago Orphan Asylum Building, 5120 S. King Dr.” Chicago: City of Chicago. 2.

[2] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 2.

[3] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 2.

[4] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 14.

[5] Moses, John (Hon.) and Maj. Joseph Kirkland (eds.). 1895. History of Chicago, Illinois. Volume II. Chicago: Munsell & Co. 393.

[6] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 14.

[7] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 12.

[8] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 2.

[9] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 14.

[10] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 15.

[11] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 1.

[12] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 5.

[13] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 23.

[14] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 26.

[15] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 43.

[16] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 42.

[17] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 43.

[18] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 44.

[19] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 44.

[20] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 45.

[21] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 46.

[22] Moses and Kirkland (eds.), 1895. 393.

[23] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 46.

[24] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 47.

[25] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 49.

[26] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 49-50.

[27] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 51.

[28] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 54.

[29] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 22.

[30] Meinzer, Helen S. 1938. “Sources and Methods of Seeking Foster Homes Used by Seven Child Placing Agencies.” Child Welfare League of America Bulletin 23 (9): 1-9.

[31] “Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

[32] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 1, 5.

[33] Chicago: An Instructive and Entertaining History of a Wonderful City. With a Useful Stranger’s Guide. 1888. Chicago: Rhodes & McClure Publishing Co. 222.

[34] Meinzer, 1938. 1.

[35] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 20.

[36] Murphy, Richard J. 1892. Authentic Visitors’ Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition and Chicago. Chicago: Union News Company.

[37] Moses, John (Hon.) and Maj. Joseph Kirkland (eds.). 1895. History of Chicago, Illinois. Volume II. Chicago: Munsell & Co. 393.

[38] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 5.

[39] “Chicago Orphan Asylum ‘Shoe Day’” 1903. Juvenile Court Record 4 (November 11): 7.

[40] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 5.

[41] Chicago Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning, 2008. 5.

[42] Meinzer, 1938. 1.

[43] “Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

[44] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 44.

[45] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 25.

[46] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 26.

[47] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 26.

[48] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 27-28.

[49] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 28.

[50] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 28.

[51] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 28.

[52] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 28.

[53] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 28.

[54] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 21.

[55] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 27-28.

[56] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 23.

[57] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 20.

[58] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 20.

[59] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 20.

[60] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 52-54.

[61] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 13, 30-31.

[62] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 66.

[63] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 66.

[64] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 68.

[65] “Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

[66] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 66.

[67] “Chicago Orphan Asylum ‘Shoe Day’” 1903. Juvenile Court Record 4 (November 11): 7.

[68] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 66.

[69] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 65-66.

[70] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 66.

[71] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 67.

[72] “Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

[73] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 16.

[74] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 16.

[75] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 16.

[76] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 32.

[77] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 44.

[78] Moses and Kirkland (eds.), 1895. 393.

[79] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 46.

[80] Seventy-Third Annual Report of The Chicago Orphan Asylum for the Year Ending November 30, 1922. 1923. Chicago: Chicago Orphan Asylum.

[81] “Orphan Asylum Group to Mark 100 Years’ Care.” Chicago Tribune (24 October 1949), p. 29, col. 3-6.

[82] Wheeler, Mrs. C. G, 1892. 67.